My atthamma, Khema, was born in 1929 in Matara. She married Mahanama, a lawyer, and later, a government Minister, and by age 27 she was a mother to three children.

Then suddenly, at age 37, she found herself widowed and left behind to support her children, her elderly mother, and herself on a secretarial salary from Lakehouse.

Atthamma, once living at the upper echelons of political society found herself building from scratch. Yet the woman I would know later in her life bore few signs of a next decade of hard knocks and tumbles.

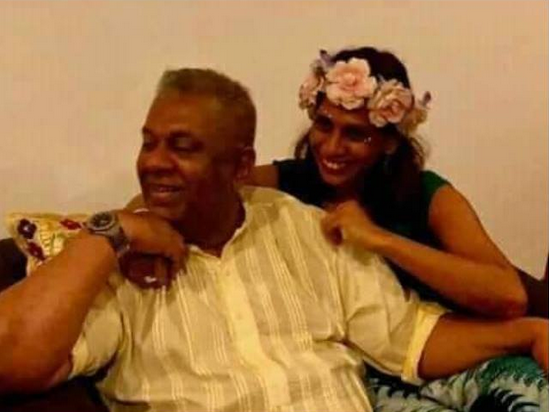

Instead, she carried with her the warmth and grace of someone who learned early on what to truly value in life; family and love.

When celebrating his 30th year in politics, Mangala shared that when at university in London he wrote a letter to his mother declaring himself to be madly in love, and to which she responded back, ‘whoever makes you happy will always make me happy.’ This simple assurance of unconditionality would have been run of the mill amongst many loving parents of history, except for its larger context.

As Mangala implied via this anecdote, shared that day in front of four Sri Lankan presidents (past and present), his mother also knew that her son’s affections were directed towards a brunette and brown-eyed brogue young man.

Yet, it did not lead her to place any caveats in her reply. Despite the Victorian morals that had been imposed upon her country, morals that some Sri Lankans even today mistake as culturally our own, my Atthamma responded with her one certain truth, the happiness of her children always mattered most.

Does it Change the Way You Feel?

I grew up in and around this same value base so much so that it shielded me for a while in an innocent and utopic worldview where people loved people and sans labels.

It took a visiting relative from the US for me to hear my first identity-related marker. I overheard her tell my mother, ‘my brother is gay too [like yours].’

Understanding this information carried an uncertain weight I went over to my mother and asked, ‘is what Aunty said true, is Mamma gay?’ My mother both answered and asked, ‘yes. Does it change the way you feel about him?’

This freshly labelled information made me take two minutes too long to ponder if I had any sudden contingencies regarding my love for someone who has always meant the world to me.

I came back and replied with the obvious, ‘no, no it doesn’t.’ And that was that. Yet, what was clear at home became complicated as the world outside stepped in. I overheard a classmate make a cruel joke at the expense of Mangala’s preference until I interjected, ‘hey that’s my uncle’, to which she apologized immediately.

While her meanness was either checked or reconsidered in the face of seeing the human-level impact, I became aware then that to others there was something weaponizable about this information.

The Mangala of it All

I can’t really say how the gay of it all operates politically in Sri Lanka beyond that, as far as I know, Mamma didn’t negotiate how his personal life was presented, nor did it seem to matter in the polls.

In fact, Mangala, to date, holds the majority of highest electoral wins in the Matara district. Part of this might be credited to my grandmother. She was well-loved and her acceptance was perhaps not to be trespassed. A testament to the power of allies. And of course, there is Mangala himself.

I’ve spoken to close supporters who remark on him as both a son of the soil and man of the world, with his incisive humour and his fearless championing for the united, democratic, inclusive, dignified and global Sri Lanka should be.

They valued that they could speak things both big and small with him, sometimes as he balanced a whisky on his knee and cigar in hand, showing a way that you could enjoy your life while doing what mattered.

And yes, perhaps it was also proximity to power. Yet I’d like to believe that the person triumphed over the prejudice against him. That the Mangala of it all, rightfully, mattered more.

Too Hot to To Touch

Still, I did also sense that for a long part of his career, when Mangala would equivocate that ‘it was his choice not to get married’, or others would use the evasion, ‘he’s a confirmed bachelor,’ that the whole truth out loud might be too hot to touch.

Indeed beyond slurs on the internet, in the media, and always most dishearteningly, on the parliament floor, threats based on his preference did come that were as equally frightening as the worries of assassination we lived with during the war.

Most alarmingly in 2013, we navigated the arrest of several of Mangala’s supporters by the government with him as the desired final target. We learned that it was being discussed to harness penal code 365 & 365A against him.

Another call for arrest came in 2015 following his UN vote to support LGBTQ UN employees maintain their family benefits. Still in 2016 under his purview, Sri Lanka voted in favour of the appointment of the UN’s Sexual Orientation and Gender Identity/Expression Special Expert.

The Work of Many, for the Benefit of Us All

(Facebook)

I have of course also heard over the years that Mangala should have done more. As Sri Lanka’s only openly gay parliamentarian, that expectation is natural.

I would only say it was in his own later years that even he basked in the freedom to state publicly and unequivocally who he was, from the clap back. ‘I’d rather be a Butterfly,’ on through to his final work on the 20 Values of the Radical Centre which featured LGBTQ rights and freedom as a fundamental pillar.

Still, what has always been clear is that it is the decades of tireless and courageous work of individuals and groups who are among the 10% of Lankans who identify as LGBTQ, along with the efforts of crucial allies, that has carried Sri Lanka to the pivotal moment we stand in today.

It is their work that unveiled the reality of long-denied harassment and legal persecution in Sri Lanka (with the most recent cases being at the Fort Magistrate in 2020).

And it is their collective work through legal process, policy, protest, parades, culture and art, that has helped foster a progressive present where 72.5% of Lankans believe LGBTQ persons should not be punished for their sexual identity. For too long, the lie that bigots have hoped would prevail is the view that equality is the cause of a few. Yet the truth is far from it as this gauge of public support shows.

After all, as is always the case in efforts for greater inclusion and equality, they stem from the values that are the best among each of us. Values that are the most human. To decriminalize love is then the work of many, for the benefit of us all.

The Time for Love

With the Supreme Court having recently dismissed unfounded criticisms and greenlit decriminalization efforts, the final step of this process is now very much in the hands of Mangala’s colleagues.

It is heartening to see that the SLPP’s Hon. Dolawatte, who has authored the private member’s bill that has presented this historic opportunity, committed to doing so based on the values of compassion and respect for all beings as enshrined in Buddhism.

It is further bolstered by the unique multiparty support publicly expressed by Dr Harini Amarasuriya in the NPP; Dr Harsha De Silva in the SJB; Minister Ali Sabry of the SLPP, and CWC leader Minister Jeevan Thondaman.

The fact that support for it would situate Sri Lanka amongst modern democracies that are our allies, including regional neighbours India and Nepal, and open new market opportunities from events to tourism and beyond should also not be discounted.

The ask then seems simple - vote for, or at least allow for, what is right. We have all faced so much hardship and crisis as Lankans. Has the time for love not yet come?

*The writer is Mangala’s niece, relaunched Mangala’s ‘Freedom Hub’ to support youth in creative enterprise development in Matara, trustee of the Samaraweera Foundation, and is the founder of the agri-food exporter Kimbula Kithul. The article was first published on Daily Mirror.