Doctors at a protest in Colombo. (Reuters Photo)

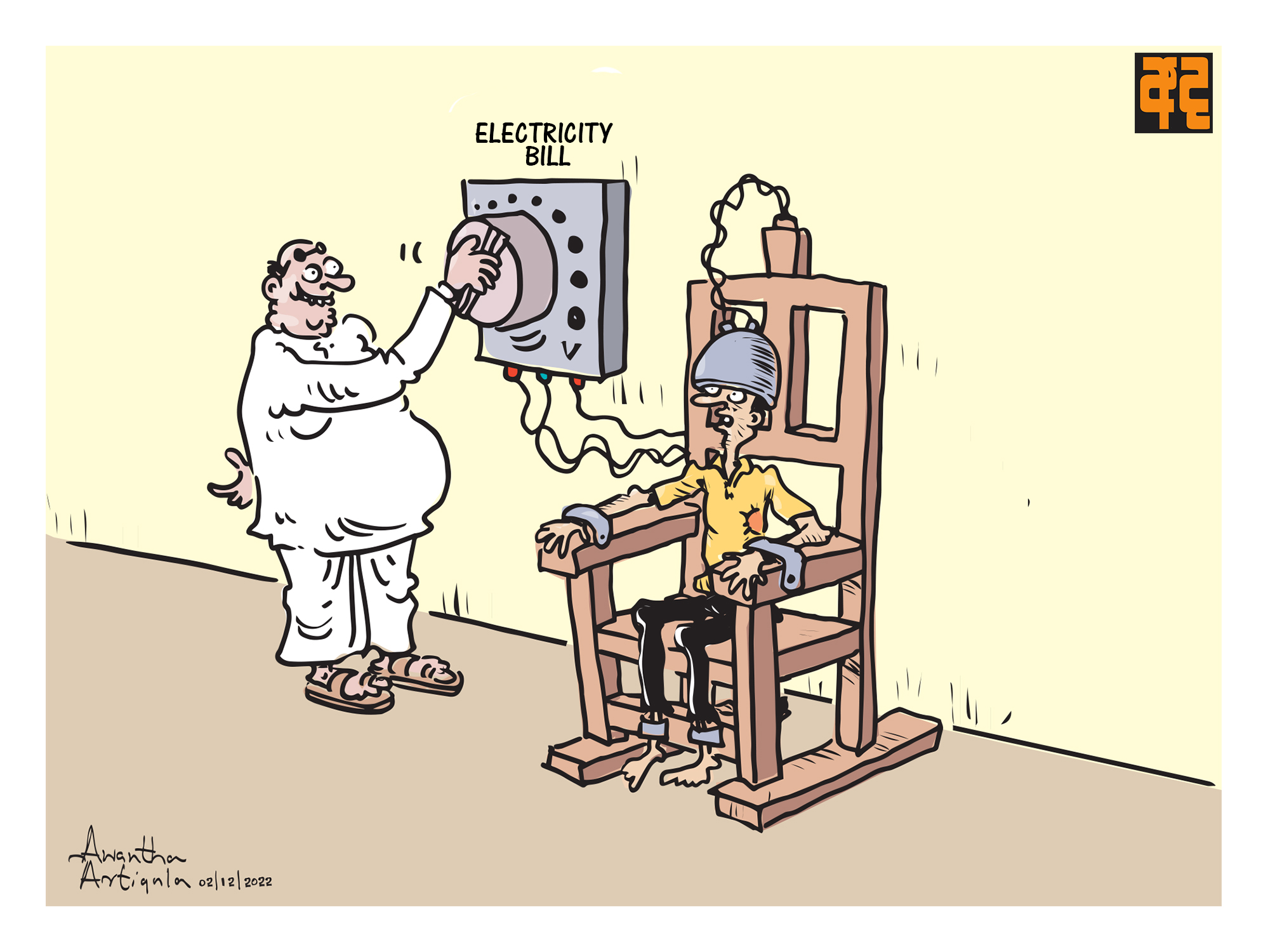

Someone in Sri Lanka, right now as I write, is distraught because a child, a parent or a loved one has died, is dying or is seriously ill due to lack of medicine and medical care.

Some die because doctors just cannot handle the overwhelming number of patients, or they simply cannot afford the eyewatering private hospital charges.

In a world of increasingly glaring disparities, we could dismiss such situations as inevitable, especially in a time of unprecedented economic stress, but such dismissal can only be defended if all necessary steps have been taken to ensure that what is possible can indeed be delivered. It is abundantly clear that this is not the case.

We are not talking about critical care necessitating costly drugs and sophisticated surgery, but non-serious medical situations that can be and have been treated successfully in Sri Lanka.

In a time of crisis hard choices must be made. Priorities must be revisited and revised. Cutbacks are inevitable even when it comes to areas that have previously been treated as untouchable. This is true of households, and it is true of nations. Consumption patterns quickly change in poorer households. Relative luxuries are shelved, but a lot of care is taken to make sure that nutrition and health are not compromised beyond certain minimum levels. It is not hard to understand.

In the end it is life that counts. It is the same with a country. A nation without people is not a nation. A nation in which people are sick and cannot get the treatment is a sick nation. No amount of debt restructuring can cure such a nation.

Professionals jumping ship

Photo illustration by Alex Gilbeaux

Falling ill even with a minor malady has become a major matter. The severe dearth of medicines and medical equipment and the growing cost of health care constitute one side of the problem.

The other side is the prevailing trend of medical professionals leaving the country, especially the most qualified and competent among them. In fact, we often hear of the accomplishments of Sri Lankan doctors currently domiciled or have citizenship in other countries. A massive loss in and of itself, but one that can easily get much worse considering that the best among those who chose to stay are contemplating leaving or have already left.

The bottom line is that we just cannot let our doctors go. Each and every one of us will one day be forced to put our lives in the hands of a doctor. A doctor is a treasure. Doctors and nurses are invaluable. We need them and they need to be protected.

Some short-sighted commentators who perhaps cannot see beyond the rupees and cents of things have seen this as a positive trend, considering the possibility of dollar and euro remittances. But what happens when the best healers leave the country? Aren’t they also the ones who set the standards? Aren’t they the principal mentors of the next generation of physicians? And since most of them are not just going abroad just for employment but are actually migrating with their families, how much will they remit, if at all? When doctors leave, there’s a very negative message being sent to everyone including other professionals: ‘leave if you can!’

Sri Lankan medical professionals are second to none in the world. This is true of doctors and other categories in the health sector such as nurses and medical technicians. They work tirelessly in less-than-ideal conditions. Despite meagre resources and having to attend on an inordinate number of patients, they are one of the main reasons why Sri Lanka’s health system is the envy of her neighbours and countries in the same or even higher brackets of economic prosperity.

While there are those who chide doctors for engaging in private practice, it is often forgotten that the vast majority of them consider their work in the state-run hospitals as their primary vocation, despite the comparatively small remuneration package.

They don’t neglect this work. They not only work but incur the wrath of some who forget that Sri Lanka is not an affluent country and are ignorant of the fact that doctors in such countries see a fraction of the patients our doctors attend to for a fraction of the salary. We should not forget that even though working under extremely trying circumstances Sri Lankan doctors are among the most accessible professionals in the world.

Let us recall the adage, ‘people leave managers, not companies.’ It is applicable here. The one thing that can make a dent in the ongoing ‘brain drain’ is strong, compelling, articulate, and empathetic leadership.

Captain lacks support from crew

The onus in this crisis-ridden climate falls directly on President Ranil Wickremesinghe. In his favour is the fact that he had the self-belief that no one else had to take control of a sinking ship. He’s steadied it, picked a course and although it is still taking in a lot of water, there’s hope that it will remain afloat.

On the downside is the fact that he’s playing a lone hand for all intents and purposes. He has no team worth that name. So, it is a solo game. He’s a man with a country to worry about walking a tight rope that is suspended over an abyss while detractors at either end tweak the rope.

To use a cricketing analogy, he’s the only one in the team who can be called a halfway decent batsman and halfway decent bowler; except that he must keep wickets, coach the team and chase the red cherry simply because the fielders seem to have sprung roots.

All the more reason for the president, handicapped as he is, to take matters into his own hands. The time for outsourcing responsibility for the health sector is long past. He can and must speak to the medical fraternity. It is unlikely they’ll listen or be moved by anyone else. The President himself has to convince them of the plans to turn things around, what has been done, what is going to be done, and why their support at this hour is so crucial for the wellbeing of the country and its citizens.

Such an address is necessary but certainly far from sufficient. The health sector serves the public, but it includes private enterprises. We have channelling services, dispensaries, all kinds of clinics, laboratories, nursing homes, care giving outfits and fully fledged hospitals. These too are faced with the same human resources problems.

On the other hand, the potential for the expansion of this segment of the sector, the setting up of new private hospitals for example, needs to be explored and facilitated. If the market is expanded leading to greater competition, private health care might become more affordable and therefore more accessible to a larger share of Lankans.

With proper policy backing, there’s nothing to stop reputed universities the world over partnering such private hospitals to train doctors, nurses, and other medical professionals. For all this, the regulatory mechanism needs to be revisited and streamlined. Again, the onus is on the president. He can and must take the initiative to create the conditions. He can and must lay the foundation to turn Sri Lanka into a medical tourism hub for the region where all these facilities are complemented by the focused and planned development of the indigenous medical system in the country.

The same goes for the pharmaceutical sector. The question of affordability can be resolved to a great extent if competition is encouraged, and mechanisms set in place to ensure standards. Resolving the criminally tragic situation prevailing in the NMRA – a direct result of interference by incompetent politicians – is an urgent must.

Conditions can be created to encourage investors, local and otherwise, to set up such industries here in Sri Lanka. The ‘greener pastures’ that medical professionals seek abroad can be ‘grown’ right here in this island.

All hands on deck

The President could start by talking to the business leaders in and out of the health sector. They need to be convinced that the problem is serious, and he is serious about not just resolving immediate issues but setting the wheels in motion to make things work in the long run.

The President has to convince the professionals that it is worthwhile fighting this battle. He must give them a reason to stay. He has to say it and do it. He must show vision and develop a plan based on this vision. He must demonstrate commitment to execute this plan. He must put together a team that can support him. He must set deadlines and work towards meeting them. Dispatching acquaintances to deputise for him in the matter of investigating random allegations will just not do it. Simply put, problems of this nature cannot be outsourced.

There’s someone somewhere grieving over a loved one who passed away or is about to because of a condition that would have been curable if curable ailments of the system had been sorted out. The dying person or the person who died could be you or me. You or I could be the person grieving. It is nothing but a tragedy when someone cannot buy medicine for a child or a parent. It is downright uncivilised in fact. Only those in such situations truly understand the dimensions of the tragedy. Unfortunately medical professionals are fighting a difficult battle, a battle which could be won if the relevant authorities opened their eyes, used their brains, and showed some kind of leadership.

Politicians don’t need our health system. When they are unwell, they seek treatment not in our hospitals but abroad. The absolute majority of our people do not have that choice. They will live or die here. Can the President deliver for them?

Krishantha Prasad Cooray