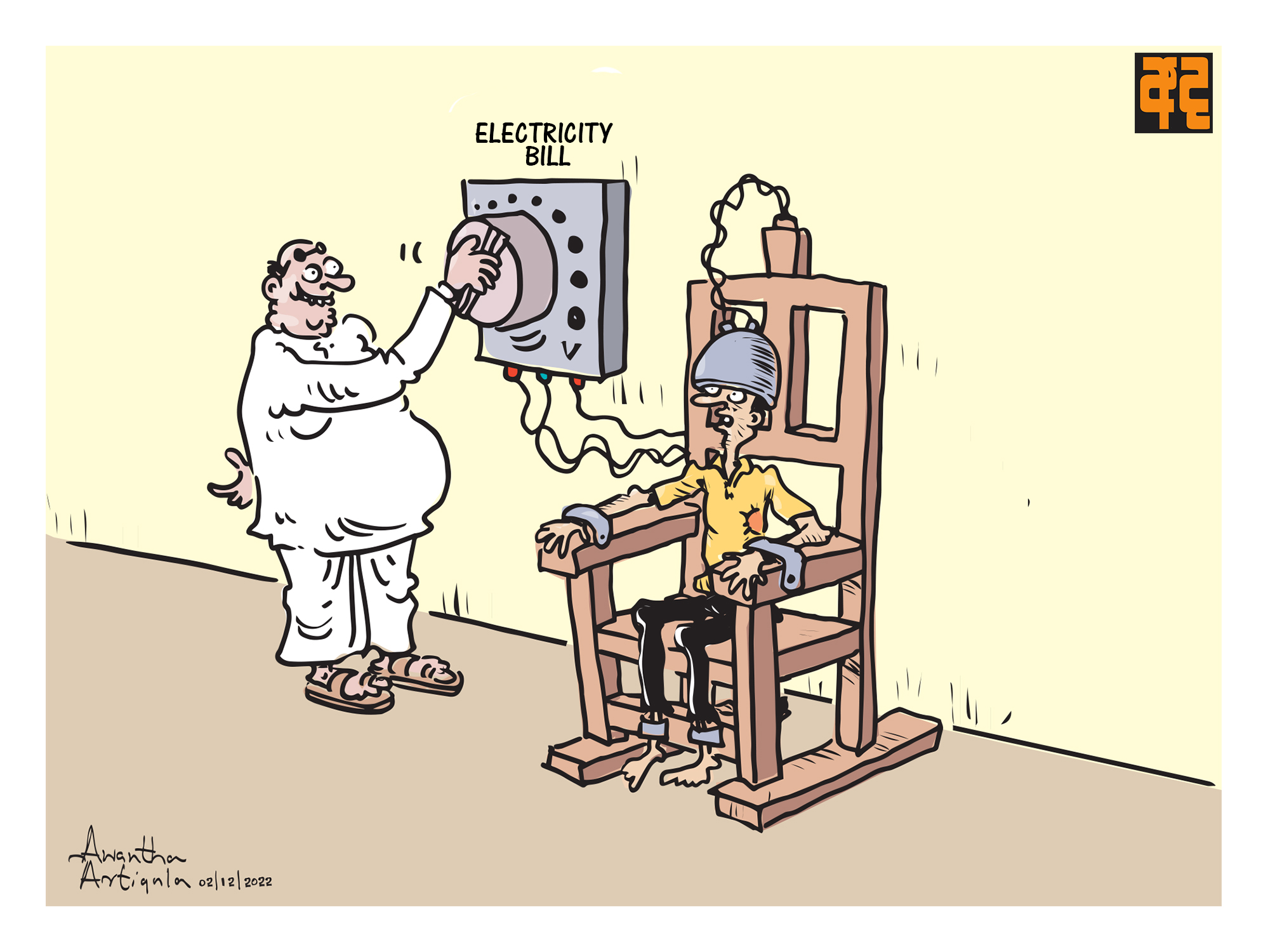

Sri Lanka's ultranationalist government has received a diplomatic shot in the arm from China as it prepares for a showdown early next year at the United Nations Human Rights

Council, the Geneva-based body where the South Asian nation has been under international scrutiny for its grisly civil war record.

Beijing's offer was featured during official talks this month with Sri Lankan President Gotabaya Rajapaksa, who was elected last November in a landslide. China promised to defend Sri Lanka's independence, sovereignty and territorial integrity "at international fora including the United Nations Human Rights Council," Yang Jiechi, China's top foreign policy official, told Rajapaksa during talks in Sri Lanka.

Yang's visit -- the first leg of a tour that included stops in the UAE, Algeria and Serbia -- came on the eve of a diplomatic victory for China. Days after the Colombo meeting, the Asian powerhouse won a seat at the UNHRC for a three-year term, which regional foreign policy observers reckon will bolster Beijing's clout in offering diplomatic protection to countries in South Asia and beyond that face international scrutiny over human rights.

The prevailing tone within Colombo foreign affairs circles suggests the expected significance of China's presence on the 47-seat body.

"China has been a consistent ally of Sri Lanka and has been a great strength in international fora," Palitha Kohona, a veteran diplomat and Sri Lanka's next ambassador to Beijing, told Nikkei Asia. "The close bonds between the two countries will continue to strengthen and there is no doubt that we will be reliable friends in international fora."

Chinese President Xi Jinping, left, talks with Mahinda Rajapaksa, right, during the launch ceremony for a $1.5 billion project to build a port city on reclaimed land in Sri Lanka's capital Colombo in September 2014 when the latter was the country's president

Chinese President Xi Jinping, left, talks with Mahinda Rajapaksa, right, during the launch ceremony for a $1.5 billion project to build a port city on reclaimed land in Sri Lanka's capital Colombo in September 2014 when the latter was the country's president

China's diplomatic guarantees come as the strategically-located Indian Ocean island looks for foreign allies in readiness for an anticipated confrontation during the next UNHRC gathering in March, the latest round to dog the country after a nearly 30-year ethnic conflict between majority Sinhalese and minority Tamils ended in May 2009. The U.N. High Commissioner for Human Rights is expected to present a critical report on Sri Lanka's post-war record on accountability and reconciliation during meeting sessions.

The Rajapaksa government has already made clear where its stands on such UNHRC scrutiny and commitments: It wants to bury the war record, with the president, himself, saying that the country needed to move on from "old allegations." The government announced early this year that it was turning its back on obligations made by its predecessor in an October 2015 resolution at the UNHRC to heal the wounds of war through "transitional justice" mechanisms. Rajapaksa has said he does not recognize that agreement.

Rajapaksa has ample reason to distance himself and his government from the 2015 commitments. He was the hawkish defense secretary during the final phase of the conflict, when the country was ruled by his elder brother, former President Mahinda Rajapaksa.

Mahinda Rajapaksa, left, smiles as he talks with his brother and then Defense Secretary Gotabaya Rajapaksa, second from left, and armed forces chiefs during a meeting to discuss the end of the country's nearly 30-year civil conflict at the president's residence in central Colombo on May 18, 2009

Names of the country's then senior political leaders, including the Rajapaksa siblings, have been implicated in war-related human rights violations, according to international human rights watchdogs. And current military leaders -- such as the army commander, Lt Gen. Shavendra Silva, and defense secretary, retired Maj. Gen. Kamal Gunaratne, both front line commanders in the final assault against the Tamil Tiger separatists -- have been accused of war crimes.

In February this year, the U.S. government made an example of Silva, imposing individual sanctions on him and denying both him and his family entry to the U.S. "The allegations of gross human rights violations against Shavendra Silva, documented by the United Nations and other organizations are serious, and credible," U.S. Secretary of State Mike Pompeo said in a statement at the time that urged the Sri Lankan government to "hold accountable individuals responsible for war crimes."

Pompeo affirmed this sanction on the Sri Lankan army chief on Wednesday during a press conference at the end of an official visit to the island nation, during which he met President Rajapaksa and other officials.

Washington's hard-line on accountability contrasts with its softer approach from 2015 to 2019 when Sri Lanka was governed by a right-of-center, pro-Western coalition alliance. The 2015 commitments, after all, were made when the U.S. was offering diplomatic backing to Sri Lanka at the UNHRC -- just as China is expected to do now in a reversal of geopolitical roles at the U.N. body. Together with the British government, the U.S. supported the Sri Lankan resolution, taking a conciliatory attitude compared to the years before 2015 when it had piled on pressure for post-war accountability. PatmanathanKokilavani holds a photo of her two children in Mullaitivu, Sri Lanka in May 2019 at a protest site remembering people missing in the country's civil war. Her daughter and son disappeared in May 2009 in the chaos of the conflict's closing days

PatmanathanKokilavani holds a photo of her two children in Mullaitivu, Sri Lanka in May 2019 at a protest site remembering people missing in the country's civil war. Her daughter and son disappeared in May 2009 in the chaos of the conflict's closing days

In exchange for that diplomatic carrot, the then Sri Lankan government agreed to establish an office for missing persons as part of its post-war obligations. The other commitments covered establishing a domestic legal mechanism to investigate alleged war crimes and reparations for victims.

According to Colombo-based diplomats, the grim details of Sri Lanka's violent past will be hard for the Rajapaksa government to sidestep at the UNHRC. In fact, Rajapaksa made a rare admission regarding this dark chapter when he told the U.N. Resident Coordinator in Sri Lanka this year that the people listed as missing since the war were in fact dead. A government-appointed commission in 2013 put the number of missing at 23,586 people, which includes the names of 5,000 government troops.

Human rights investigations have also fingered the Tamil Tigers, the separatist group that fought to set up an independent state in the island's northern and eastern parts, for committing alleged war crimes in the conflict, where over 100,000 people were killed.

Seasoned analysts are casting doubt on alternatives Sri Lankan authorities have floated to make up for their retreat from the existing U.N. commitments.

"While the Rajapaksa government has promised it will pursue some of the same policy goals through a new -- as yet non-existent -- 'domestic mechanism,' there is no chance such a process, should it be established, would address the legitimate demands within and outside Sri Lanka for truth and justice for the crimes committed by all parties to Sri Lanka's terrible civil war," said Alan Keenan, senior Sri Lanka analyst at the International Crisis Group, a Brussels-based think tank.

Sri Lankan human rights campaigners are just as gloomy. "The 2015 resolution created expectations and some people benefited from the space to talk about the violations during the war," said Sherine Xavier, director of The Social Architect, an independent human rights watchdog, "but that gave way to disappointment and people lost hope because little was achieved."

She added: "China was there before 2015, helping the Sri Lankan government at the UNHRC from behind the scenes. Now they will do it openly, from the front."