People using existing road at the Western end of Lankagama - photo courtesy Lakdasun trip

People using existing road at the Western end of Lankagama - photo courtesy Lakdasun trip

That the village is over 500 years old is disputed by Environmentalists. A senior activist posting on FB said it is sheer romanticising of the village. Neluwa Divisional Secretariat (DS) sources accept the village is around 300 years in existence. Lankagama villagers say there are around 700 families. Neluwa DS website says the population of Lankagama grama niladhari area was 655 in 2018. Perhaps, the figure 700 quoted by villagers is the present number of “people” and not “families”. Geographically, Lankagama grama niladhari area is one of the largest in Neluwa DS division.

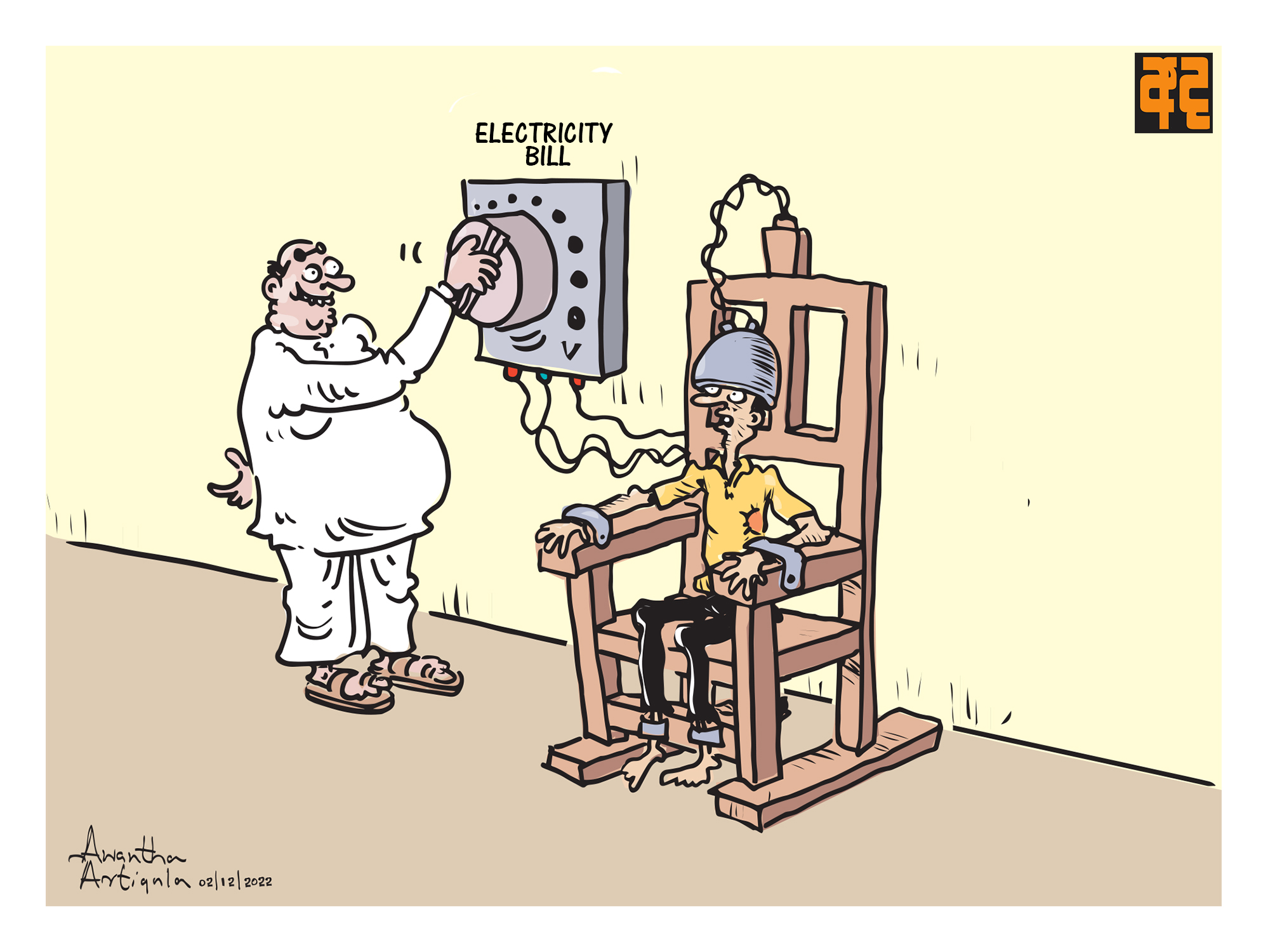

Environmental activists claim the new Rajapaksa government is using security forces to widen and carpet the Lankagama – Neluwa road to construct tourist hotels in Sinharaja. Yet, there is no clear and confirmed information on hotel construction. An NGO, “Centre for Environmental and Nature Studies” (CENS) writing to the President, the Ministry of Environment, the Central Environment Authority and Wildlife Department claim the road that is being constructed is “illegal” and is within the Sinharaja World Heritage Site, a good enough reason for them to write to the UNESCO as well.

Environmentalists believe the environment cannot be compromised for “human development”. A very short comment I posted on FB regarding this controversy, was immediately responded to by a very respected senior Environmentalist. He was very frank asking, “Do you say we have to compromise a virgin rainforest, which is also a national and a world heritage for human development?”

This, in fact, is the main issue. People in the village want their road done. Environmentalists don’t. People in the village believe widening the existing road is a long overdue necessity for them. Environmentalists don’t. People in the village believe widening the road will not be a threat to the national and world heritage site. Environmentalists don’t. People in the village who want the road done, live adjoining the Sinharaja forest reserve. Environmentalists don’t.

On 28 November last year, Principal of the Lankagama model school organised a felicitation ceremony for his own teaching staff, attended by the Neluwa DS, parents and few others. At this ceremony he said some years ago, most teachers came late on Monday from distant places, roughed out the whole week and left early on Friday. Now, most teachers are from neighbouring villages. They walk to school every day, a distance of about 06 to 08 kms each way. They have been exceptionally helpful and committed in improving the education of Lankagama children, a service that needs to be appreciated. The school has around 175 children in daily attendance and has classes up to G.C.E O/L.

An isolated village where teachers must walk many kilometres to school and back, says a lot about lack of basic needs. Improvement in the quality of life, easy access to public utilities and services, better and improved linkages to markets, are all part of development people want. They in fact are the most basic needs in present day human life. All these depend on good and efficient transport and commuting. That is why roads become an indispensable part of daily life. Lack of, absence or denying of basic needs, define poverty in its crudest manner.

What environmentalists stand for is this crude poverty, in the name of safeguarding the environment. That is precisely the undertone the question posed to me carried; we don’t compromise the environment for human development.

This hard line, blank position compels environmental NGOs to draw on their own assumptions as “facts” to argue their case. The “illegal road” mentioned by CENS as running through Sinharaja, had been there for many decades as a gravel road, used by villagers in Lankagama and in neighbouring areas. Out of the 18 kms, only a very short distance of about 03 kms run through Sinharaja forest reserve and that too in short segments. Short or long distance, any path people use for daily commuting over decades without any restrictions and objections recorded, becomes legal by default. In 2010, this road was paved with concrete, from funds allocated by State authorities through Neluwa DS. What then is “illegal” is therefore never imaginable. Ironically, it is such factually distorted and wrong information these environmental NGOs often provide to State authorities and international organisations to gain legitimacy to their protests.

That apart, getting back to the dichotomy “human development vs environment”, never in the history of human civilisation has progress been achieved, without breaching and trampling nature and environment. The 2,500 BC Indus river civilisation Mohenjo-Daro and Harappa, was a fire burnt brick based civilisation. Without doubt, clay was dug up in mega quantities for bricks and forests were cut down to burn bricks in constructing big and orderly cities and roads. So were all other civilisations, whether constructions were wood, or iron based.

In ancient Ceylon too, construction of giant tanks for agriculture would not have been possible without breaching and damaging the environment. Culawamsa, the Pali chronicle says, King Parakramabahu restored tanks and built new tanks, all totalling 163 major tanks. One that covers an area of 30 sq.km is named after him as “Parakrama Samudraya”.

In post independent Sri Lanka all “development” initiatives from colonisation schemes to hydro-power projects came with restoration of reservoirs, construction of large dams and tunnelling. From Gal-oya in 1952 to accelerated Mahaweli development in 1979 and Samanala weva project in 1986, all such projects stepped on the environment. In the past, Gal-oya, Kantale, Rajanganaya and other similar developments were technically approved, but never had EIAs and none would know what environmental damage they brought about. Fact nevertheless is, new habitats, new eco-systems have evolved thereafter.

We have come a long way from Parakramabahu and from Gal-oya. We have also learnt much from the accelerated Mahaweli development programme. We have expertise, technology and past experience to “plan development better and save the environment better”. What is still lacking is a new people centric thinking in environmental activism. Worst is that most environmentalists have also turned Sinhala-Buddhist “patriots” on the run. They and their NGOs also believe “people are outsiders to environment” and human development is no priority. They work on the premise; it is their duty to fight legal battles to stop any project they decide should be stopped and protest any they believe cause destruction.

We need to come out of this primitive thinking. This thinking in environmental NGOs as exhibited in Lankagama contributes to sustained poverty, denying development. We need to know, “human development” cannot be compromised as much as the environment cannot be played about, as “Climate Change” clearly teaches. We therefore have to learn that “protests” are no answers. Though isolated, Lankagama by the side of Sinharaja rain forest is a classic case that challenges these protesting environmentalists to come up with their “solution” to the conflict without denying the people their right to better and improved life.

Environmentalists have to leave agitating against single, isolated issues and propose a “National Environment Policy” that should cover everything from urban air and sound pollution to landslides, from domestic waste disposal to surgical and industrial waste, from coast conversation to reforestation and management, from urban planning to town and housing development and honouring all international conventions the SL government is a signatory to and have ratified and should ratify. It should include regulating and monitoring agencies and have a special complaint investigating mechanism, independent of ministries and politics.

Such cannot be drafted and concluded by “experts” alone. This requires an open social discourse at every stage of its drafting. It needs to draw the participation of social activists and community leaders. In short, when the “National Environment Policy” becomes law, it must be a social product owned by the People.

The ancient style of taking up issues as and when they become politically important and worth for environmental NGOs to agitate and protest is no more valid. Environmentalists must leave those old sectarian practices and face the challenge of drafting a “National Environment Policy” with people’s participation and take over the responsibility of social monitoring and lobbying for answers within the national policy.

In post COVID-19 global and national life, this is a new era with a new challenge demanding new answers. An era, where strengthening democracy is the beginning. Hence social participation and ownership in planning and implementation. I would not know if environmentalists could stand up to this new challenge. Lankagama therefore would be the first test for environmentalists in post COVID-19 Sri Lanka.

2020 August 21