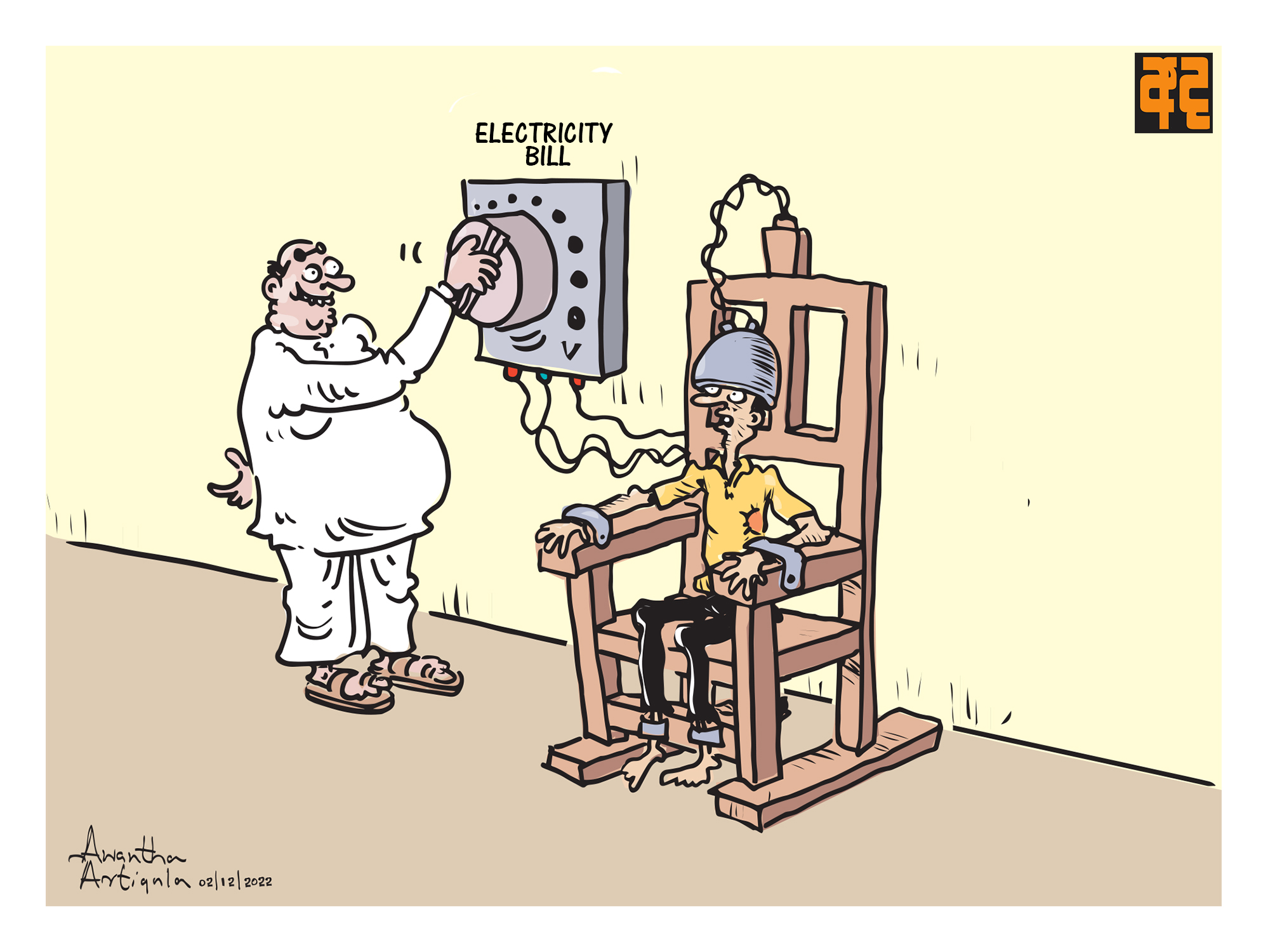

Sri Lanka's central bank trumpeted the country's settling of a maturing $500 million sovereign debt on Tuesday, affirming the ultranationalist government's decision to use its scarce available foreign currency reserves to assuage overseas bondholders while its beleaguered public takes another economic hit.

An 11th-hour financial lifeline from India allowed some breathing room while the funds were released by Nivard Cabraal, who secured a nominal cabinet minister's position following his appointment as the governor of the Central Bank of Sri Lanka in late 2021. New Delhi's offer of a $400 million currency swap with the Reserve Bank of India and a deferment by two months of repayment of a $515 million loan that Colombo owes the Asian Clearing Union, a network nine central banks in the region, followed ministerial-level discussions between the South Asian neighbors.

"All the transfers have been done," Cabraal was quoted as telling Economy Next, a local online financial news platform, on Monday evening. "On the 18th they will all get the payments at the correct time."

The Indian offer to the Sri Lankan government of President Gotabaya Rajapaksa, who is overtly pro-Chinese, came as the supposedly-independent central bank pursued more desperate measures to ensure it had dollars in hand as Sri Lanka's usable foreign reserves plummeted to $1.6 billion -- barely sufficient for one month of imports -- as 2021 drew to a close. Early this month, the central bank sold half the country's $382 million worth of gold reserves. Days before, it had requested that two state banks stop opening letters of credit in a bid to halt the outflow of dollars for imports to secure its reserves for the Jan.18 international sovereign bond payment.

But a promise of a more generous than expected package from India -- a $1 billion credit line for essential food and medicine -- that follows a 10 billion yuan ($1.5 billion) swap with the People's Bank of China in late December offers only marginal relief. After all, Finance Minister Basil Rajapaksa, younger brother of the president, has admitted that the country needs to pay $6.9 billion in total foreign debt this year, including a $1 billion sovereign bond maturing in July and interest payments to other foreign lenders.

Central Bank data at the end of 2021 revealed that reserves had swelled to $3.1 billion on the back of the Chinese swap of $1.5 billion. But Cabraal has been evasive about whether the Chinese swap placed restrictions on its usage, raising questions among those in commercial banking circles here that the Chinese relief might not qualify as usable dollar reserves.

Not surprisingly, a chorus of business leaders, respected analysts and opposition parliamentarians urged the government to reconsider its stubborn stance of paying the bond at any cost and explore an alternative route: restructure the debt or go to the International Monetary Fund for a relief package.

"This time it is an insolvency issue, including liquidity, and you cannot solve the fact that Sri Lanka is still insolvent through bridge-financing like swaps," Harsha de Silva, an economist and opposition parliamentarian from the Samagi Jana Balawegaya party, told Nikkei.

Cabraal's reluctance to go to the IMF is due to ultranationalist sentiment, which is shared by others in the Rajapaksa government who regard help from the multilateral lender as undermining sovereignty. Sri Lanka has sought IMF relief 16 times in nearly 56 years, an unenviable record that comes second only to debt-strapped Pakistan. However, Sri Lanka has not defaulted on its international debts since it first claimed foreign loans.

Sri Lanka's debt profile reveals its economy -- valued at $81 billion of gross domestic product in 2021 -- sinking in a sea of red, with the debt to GDP ratio rising from 85% in 2019 to 104% in 2021. It is a grim picture that prompted global ratings agencies such as Fitch Ratings, Moody's and Standard & Poor's to downgrade Sri Lanka's sovereign ratings further into the territory of junk, much to the chagrin of Cabraal.

S&P cut Sri Lanka's ratings from "CCC+" to "CCC" at the start of the new year, following Fitch, which slashed the ratings from "CCC" to "CC" in mid-December, effectively extending the lockout of Sri Lanka from accessing international capital markets since early 2020. "Cumulative foreign-currency debt service, including interest and principal, amounts to about $26 billion from 2022 through to 2026," Fitch said at the time.

Analysts conceded that Sri Lanka's debt spiral, which the Rajapaksa administration inherited from the dysfunctional government it defeated at the November 2019 presidential elections, has worsened following the outbreak of COVID-19. The pandemic has sapped the flow of dollars from the island's formerly buoyant tourism sector, which in 2018, its best year on record, generated more than $4 billion.

A drop in migrant worker remittances, and the country's multi-billion-dollar trade and current account deficits, have made it even harder for the Rajapaksa government to meet its annual debt payments. Foreign reserves had plummeted from $7.9 billion at the end of 2019 to $1.6 billion usable reserves by November 2021. The central bank's provisional calculations reveal that foreign remittances sank by a staggering 22.7% last year, going from $7.19 billion in 2020 to $5.49 billion in 2021.

That drop, according to commercial banking sources, indicates migrant workers shifting from remitting money through official banking channels due to an artificial dollar-to-Sri Lankan rupee exchange rate currently in force, whereby the central bank wants commercial lenders to pay no more than 210 Sri Lankan rupees for $1. Holders of dollars, meanwhile, can receive almost 250 Sri Lankan rupees per dollar in a thriving black market on Colombo's streets.

The growing scarcity of food, fuel and medicines on which Sri Lanka's import-dependent economy survives, and a spike in inflation during 2021, has prompted warnings from some quarters that the country is on the cusp of having years of prosperity wiped out. Inflation in December was up more than 10% from 12 months earlier.

"Economic decline could result in a complete breakdown of law and order," warned the Bar Association of Sri Lanka, an influential independent body of Sri Lankan lawyers, in a terse statement. "Serious repercussions flow from growing financial hardships that have to be borne by citizens."

Similar alarm bells are ringing in some diplomatic circles in Colombo, embassy sources have revealed to Nikkei. A statement by the Canadian mission to its citizens in Sri Lanka on the eve of the bond payment conveyed the sense of a country on the brink.

"Keep supplies of food, water and fuel on hand in case of lengthy disruptions," the statement says. "Long line-ups may be experienced at grocery stores, gas stations and pharmacies."

(Nikkei)