In the aftermath of the Easter terror attacks, the role and intervention of the Human Rights Commission of Sri Lanka (HRCSL) has assumed added significance, as the country battles old demons and faces new uncertainties. met the Chairperson of the HRCSL, well-known academic and activist Dr. Deepika Udagama, for an in-depth look at the myriad challenges facing the country.

Q In the last two months Sri Lankans witnessed multiple terror attacks, communal violence and a state of emergency. How has the HRCSL responded to these crises?

We view these events as a continuum. We knew the authorities would approach the Easter attacks as a national security issue. But when the Commissioners met on April 22, the day after the attacks, we recognized that such violence must also be dealt with from a human rights perspective. We realized the aftermath of the attacks would bring social tensions based on religious divisions.

Q On April 26 the HRCSL released a statement warning people of a “cycle of hatred” and urging them to avoid hate speech and violence. But has the cycle of hatred already begun?

For two weeks the country was relatively calm, which was a bonus because over the decades violence and retaliation was the norm. This showed the public had matured, and had realized that counter-violence could spiral out of control. But on May 13, violence erupted. It was orchestrated violence, not spontaneous retaliatory violence. These manufactured cycles of hatred could have had political and commercial purposes. But they were not naturally spontaneous. People have learned from past bitter experiences.

When such incidents happen, communities get stereo-typed. After the 1983 anti-Tamil riots, the world viewed the sinhalese as being violent, discriminatory and bigoted. During the war, many Tamils were seen as LTTE members or supporters, and the Tamil community and terrorism were viewed as one and the same. Currently, the Muslim community is being similarly branded.

So while the terror attacks must be dealt with legally, there are larger social and political issues that cannot be combated through the prism of national security. The natural inclination towards suspicion and division should be broken by policy. But certain policy decisions have been fetters to uniting the public. These cycles of violence have made us a wounded people. There were two southern insurrections, a 26-year-old war, and now these attacks. But impunity has been the norm, and people have’t seen justice since 1971.

Any form of censorship has to be well thought through and rationalized, under constitutional or freedom-of-expression terms

Q Are you saying that most people are tolerant and want peace, but the forces of division and hatred are dictating terms?

This is a very big question, which needs a well-examined answer. Perhaps people are not highly enlightened about pluralism, or are tolerant and respectful towards one another. But the average person recognizes the cost of violence. Despite their suspicions and stereotypes, people wish to desist from violence, knowing very well its consequences.

But the orchestrated violence of May 13 was different. Particularly the orchestrated efforts by the media. The HRCSL sent guidelines to the electronic media because the imagery being projected was having a negative public impact. People were fearful of sending their children to school. This is remarkable in a country which has seen so many cycles of violence. We’ve had national exams and general elections throughout that violence. But suddenly people reacted in a totally different way.

The media should have reported the news without causing sensationalism and alarm. A lot of issues today are orchestrated for political and commercial interests. But the media, perhaps for political or ideological reasons, are not playing a responsible role. There are those media which are more sensible and responsible, but there are the rabble rousers too.

Q The HRCSL wrote to electronic media heads about promoting disharmony, reporting gossip, and carrying traumatic footage.

And also about being sensitive towards the victims and their families.

Whenever a country has moved away from crises and is working towards a more humane society based on democratic principles and values, they move away from the death penalty

Q Did you get a response?

No, we have not got any response challenging our guidelines. But the Free Media Movement (FMM) picked up these guidelines and have urged all media to abide by them for the public good. Events must be viewed from a longer-term perspective, and not as day-to-day events. The HRCSL is appealing to the media to develop a responsibility towards long-term solutions. We are also drafting guidelines for the print media. We had a conversation with editors about our concerns and their challenges. We will continue to work on the media, and we believe that peace-loving citizens should be heard.

Q We also saw the government blocking social media on grounds that they wanted to prevent the spread of false news. What is your view on this?

We need to understand how social media works. Some say that despite the possibility of immediate provocation and mobilizing people for violence, social media should not be censored at all. But when the Digana violence happened the government suspended social media for three weeks, and many members of the community told us it was a life saver. The crowds came from outside, and were organized through social media. It was orchestrated violence, not spontaneous violence by local populations. Also, social media lacks effective tools to control and censor hate speech. They claim they do, but where there is widespread violence, it’s clear social media does not. When the New Zealand massacre was streamed, the Prime Minister called for international support to control it.

So this requires more study, because the HRCSL does not approve of broad censorship. Any form of censorship has to be well thought through and rationalized, under constitutional or freedom-of-expression terms. So we recognize social media’s potential, but there’s also a down side.

Q In the HRCSL letter to the IGP, you mentioned that the police and security establishment did not take preventative measures on May 13. So while there’s orchestrated violence, the authorities too are not protecting citizens, as highlighted in your letter.

Exactly. Even if there was orchestrated or pre-planned violence, effective law enforcement could have prevented it. There’s no contradiction between the two. We saw unpreparedness on the part of the police. The security sector works with intelligence, and reports would have indicated possibilities of violence after April 21. So we expected a state of high alert. But that was lacking, and there was a relaxed approach. The public reported people congregating on motorcycles. Most were from out of town, with some locals. When people called 119 and 118 `there was no response. Our investigations revealed there was unpreparedness. It would be very upsetting if it was not unpreparedness, but intentional relaxation.

Q Your letter also highlighted occasions when the police was unable to contain the violence, or did not intervene when they could have.

It’s a combination. At first it was unpreparedness, and there were no reinforcements. But we also saw that when they could intervene, they did not. But we are made to understand that they were outnumbered. And in Bingiriya the police caved in to political interference. I visited the Bingiriya Police Station and we saw the documents. Some suspects were arrested for the violence, and a large crowd gathered outside the police station. The police has the powers to disperse crowds and get reinforcements. They could have used their organizational strength from surrounding police stations, the STF, and army camps not far away. But instead, they quietly moved the suspects to another police station.

Q So does the May 13 violence require further scrutiny, like the PSC appointed to investigate the April 21 bombings?

We think so, and we hope so. There are ongoing police investigations, but we’re unsure if they will investigate the genesis of the violence. This was orchestrated violence, where outsiders, and some locals, were involved. They come in droves, and there’s a certain pattern to how they converge. If it was purely retaliatory, the violence would have erupted soon after April 21.

There were well-organized and seemingly well-funded hate groups operating. They function openly, and by their own admission seem to be politically connected. This is worrying. So a very in-depth inquiry is needed.

Q We have seen the police and military cracking-down violently on large student and worker protests. If they can take such measures against protests, why not take sterner action against orchestrated communal violence?

You have to ask the police. What is their preparedness? What techniques do they use for crowd control? How do they differentiate between a student protest in one location and violence that keeps spreading? One of our first inquiries was the attack on the NDT students at Lipton Circus. Video footage showed students being beaten and getting badly injured.

In a democracy, democratic crowd-control methods are absolutely essential because of the right to protest. We highlighted that disproportionate brute force must be addressed through better training, sensitizing the police and identifying the tendencies of local protesters. Historically, student protests and union actions are a constant factor. But we could not elicit a technique or manual being used in police training methods.

So we recommended that the police prepare a manual with help from the National Police Commission (NPC). But instead of accepting our recommendations, the police challenged them in court. State institutions should not view each other as adversaries. When independent commissions makes recommendations, reasonable engagement must follow, and mistakes must be pointed out. But because of antagonism, the system of checks and balances does not really work. This is compounded by the dimension of politicization. There’s an ethos and a mindset that one is not completely free to act professionally. That one must give into these various pressures.

Q There’s concern that the government will use emergency regulations to suppress the democratic rights of citizens.

There’s always a tension between special laws and human rights. The HRCSL recognizes that April 21 required special measures, but they must be temporary and proportionate to the threat. For example, it would be excessive to use emergency powers against a student protest.

From 1971 to 2011 we have lived more under emergency. That’s the tendency. But in Digana, emergency was declared, but was removed quickly. So we hope this time too emergency would be lifted as soon as the immediate security threat is dealt with. This balance can be found because we have a good body of Supreme Court (SC) jurisprudence which tells us how emergency powers are to be balanced with the rights of the people.

In a democratic system of governance the legal system is supposed to be based on liberal values. But we’ve taken on merely the trappings of that system and not its substantive values and norms

Q The HRCSL wrote to the Bar Association of Sri Lanka (BASL) questioning the ethical standards of some lawyers in regional bar councils, and called for corrective measures. Why is there such a drop in legal ethical standards?

Certain members of the bar not appearing for those they view as the “other” did not happen overnight. It reflects a deep-seated crisis within the legal community, and how we view the rule of law. The BASL responded saying they stand for the rule of law, and that no resolutions were passed to the contrary. But we continue to hear reports of unofficial agreements in regional councils. Even decades ago, mainly provincial bars have refused to appear for certain types of accused. For example, those accused of child abuse. Now it’s taken a racist overtone.

In a democratic system of governance the legal system is supposed to be based on liberal values. But we’ve taken on merely the trappings of that system and not its substantive values and norms.

Q You have many years of experience in legal education. Is this happening due to a drop in standards in legal education?

It is a problem with legal education, but legal education alone cannot fix it. Our schools don’t impart liberal values or ask questions on equality, justice, rights, or encourage the skills and capacity to engage in open debates, discussion and discourse without seeing the enemy in the other. Our school system is very anti-democratic. The classrooms are very anti-democratic. Students attend ethnically and religiously segregated schools.

So the vast majority of children enter legal education thinking of life in black and white. In legal education they are suddenly taught principles of justice, equality, fair play, impartiality, independence and principles of natural justice. These are principles needed for professional life, but they are extraneous to one’s thinking. It’s never absorbed into one’s being. You may think professionals have to respect these principles. But very easily young professionals feel they can cut corners, and their primordial values surface.

Q So should law degrees be made into post-graduate degrees, like in some countries?

Yes I think it should be. Because law is derived from so many other sciences and theoretical backgrounds, that to understand it in its pristine purity and the potential it offers a society, it’s better to have a background in some other area.

As a law student in my first year I was taught constitutional law. That’s a long jump for someone just out of school. Whereas if you are grounded in political theory, and have some life and work experience, it has a deeper meaning.

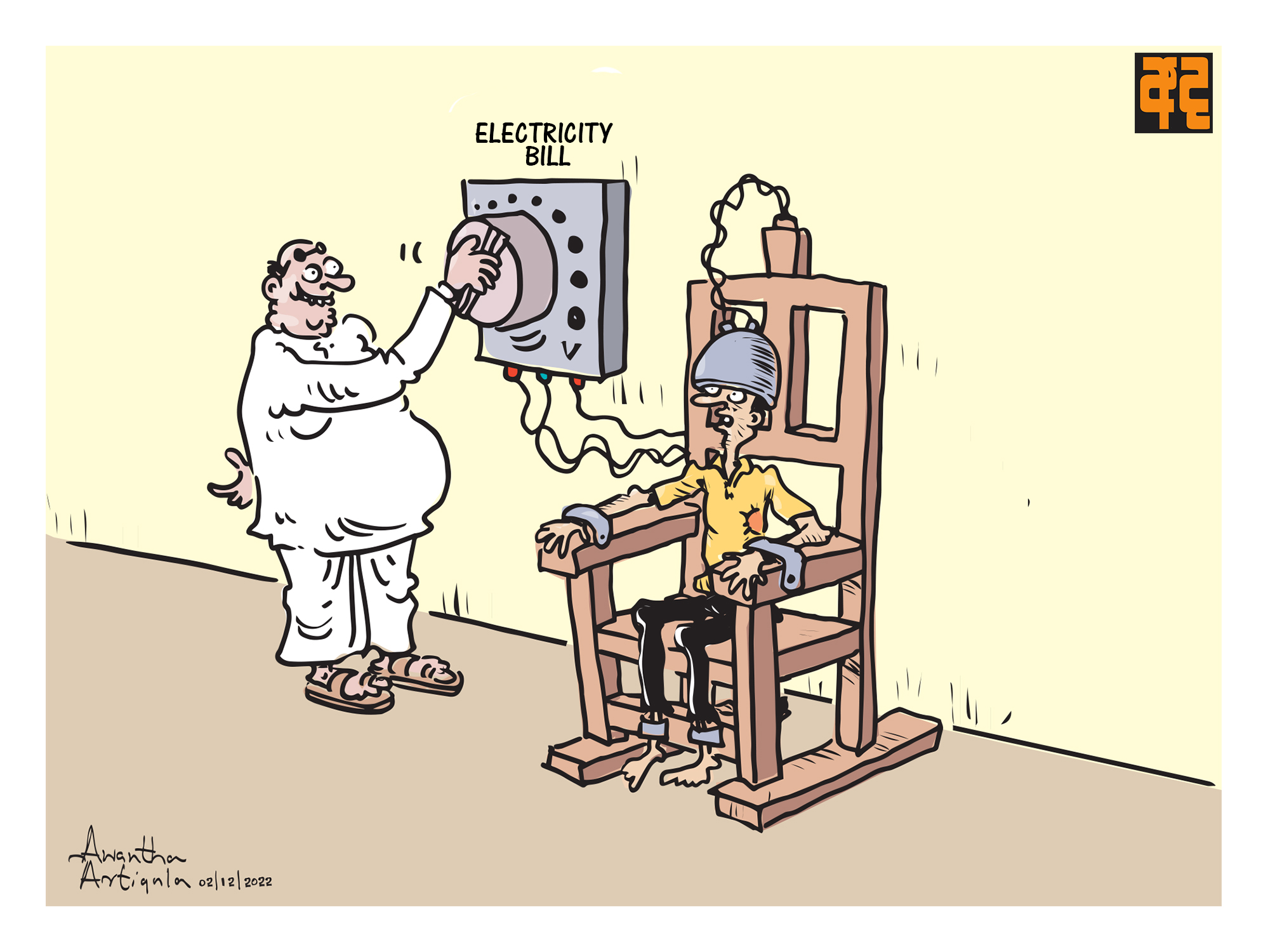

Q Recently there’s been talk in the political arena about re-implementing the death penalty to combat crime. How do you reconcile this with the right to life?

If speaking about the right to life of the person condemned, then you cannot reconcile the two. But you also cannot reconcile the death penalty with larger social interests. Many think the death penalty is in the public interest.

The HRCSL’s first recommendation to the government in 2016 was to abolish the death penalty. Whenever a country has moved away from crises and is working towards a more humane society based on democratic principles and values, they move away from the death penalty.

A society is judged by how it treats the most marginalized and vulnerable. How does a society view people who have committed unspeakable crimes? Do we treat them with vengeance, or do we try and understand that for various reasons they have become anti-social, and need to be put on the right path? Killing someone in our name is not the solution.

Most countries that abolished the death penalty recently are from Africa, like Rwanda and South Africa, which experienced terrible spirals of political violence. In our subcontinent Nepal emerged from an internal conflict and abolished the death penalty. So when a society is moving away from conflict and onto something more idealistic, one finds these markers.

Q So in that sense Sri Lanka is an exception.

We have been unable to make up our minds. Sri Lankans don’t want to return to war. But we’re not quite sure how to create a society that deals with conflict in a more peaceful and humane manner. How do we eschew discriminatory practices and ethnic politics, and deal with identity politics more intelligently? We are very confused. This a reflection of these contradictions.

Q Regarding constitutional reform, what do you feel about Buddhism having the foremost place in the constitution in relation of the idea of equal citizenship?

The HRCSL in its proposals for constitutional reform in 2016 sought fundamental constitutional principles to be enshrined in the constitution. We said it was important to recognize non-discrimination and equal citizenship on the basis of ethnicity, religion and so on.

Sri Lanka is undoubtedly profoundly influenced by Buddhist philosophy and cultural practices. But previous constitutions have, through fact or perception, made minorities feel excluded. Ethnic and religious pluralism must be dealt with intelligently, while realizing the country’s cultural realities. Perhaps if our religious divisions were historically not so deep, and there was amity, the Buddhism clause would not elicit much of a response. But since pre-independence, our politics was based on division. First ethnic division, and now religious division.

For a constitution to work people must take ownership of it. The HRCSL maintains that the people, and not politicians, should play the major role in constitution making. The Lal Wijenayake committee report on public consultations should be at the core of constitutional reform, because it demonstrates what the people want.

Constitution making offers society a new beginning. These are moments for idealism, not everyday bitter mundane politics. These are moments for poets and philosophers. Not hardcore politics. If and when we understand that, we might find at least that constitutional peace. So for Sri Lanka the challenge is to develop a constitution that everyone feels a sense of belonging to and has ownership over.

Sri Lanka is undoubtedly profoundly influenced by Buddhist philosophy and cultural practices. But previous constitutions have, through fact or perception, made minorities feel excluded

Q There’s also debate on whether Economic, Social and Cultural (ESC) rights should have the same status as Civil and Political (CP) rights. Should ESC rights be justiciable?

Absolutely. The HRCSL’s constitutional proposals advocate for giving parity to both groups of rights. Human life cannot be divided into parts, with certain parts remaining more important than others. Everything in life is interconnected. Human rights are about human existence with dignity. You cannot compartmentalize and say one’s CP rights are more important than the right to food, education, or dignified employment. You can’t find political voice unless you have ESC rights. A good education gives you more voice, and allows you to enjoy freedom of expression even better. If you lack good healthcare, and have poor nutrition, it impacts on everything else.

In our work we look at the indivisibility of rights. All rights are interconnected and must be justiciable. Every right must have a remedy. ESC rights don’t require more funds and resources than CP rights. The most expensive right is franchise. So if we spend billions on four types of elections, why are we so hesitant to include the right to education or healthcare? And it’s a misconception to imagine the State must provide everything free. The State must simply create an environment where you can enjoy these rights. We have to look at human dignity holistically.

Q Do you think the recent tensions and conflicts are due to all communities feeling a sense of alienation and threat?

I think there’s definitely confusion. The sense of being threatened and alienated stems from confusion regarding the basic fundamental principles on which this society runs. We need voices of clarity to help us live in a diverse society. This is how a society resolves suspicions. The political establishment has the biggest responsibility to provide leadership and tell people how to deal with these issues.

The HRCSL sees this as a moment of opportunity. Everyone has been shocked out of complacency and many issues that were earlier under wraps are now being discussed. People need guidance, with no adding to the confusion.

Take the swords issue. An explanation must be provided rather than people left to speculate. There must be space to discuss and debate the issues that bother us. For example, dress has become a big issue. There is confusion on how to negotiate cultural and religious matters.

At this moment people need clear thoughts, clarity, and voices of decency which provide reassuring and firm leadership. It must come from political leaders, community leaders, and the media.

Q So you see an opportunity in this crisis?

Absolutely. This is a wonderful opportunity, but we are not grasping it. Instead we have adopted a blame game and are labeling and categorizing people. There’s a terrible acrimony surfacing. The first two weeks after the blasts gave us a hint of these possibilities. We heard voices of sanity. But May 13 onward has been very confusing to the people.

Democracy is about people having representation when they are fearful and confused. It’s not a time for election and divisive politics. All political representatives should have united and addressed this as a national calamity. After everything is settled they can engage in electioneering. When people witnessed the goings on in parliament, they got further confused. There was no cohesion. But if we grasp the moment with foresight, there are many possibilities.

Gihan de chickera

(dailymirror.lk)